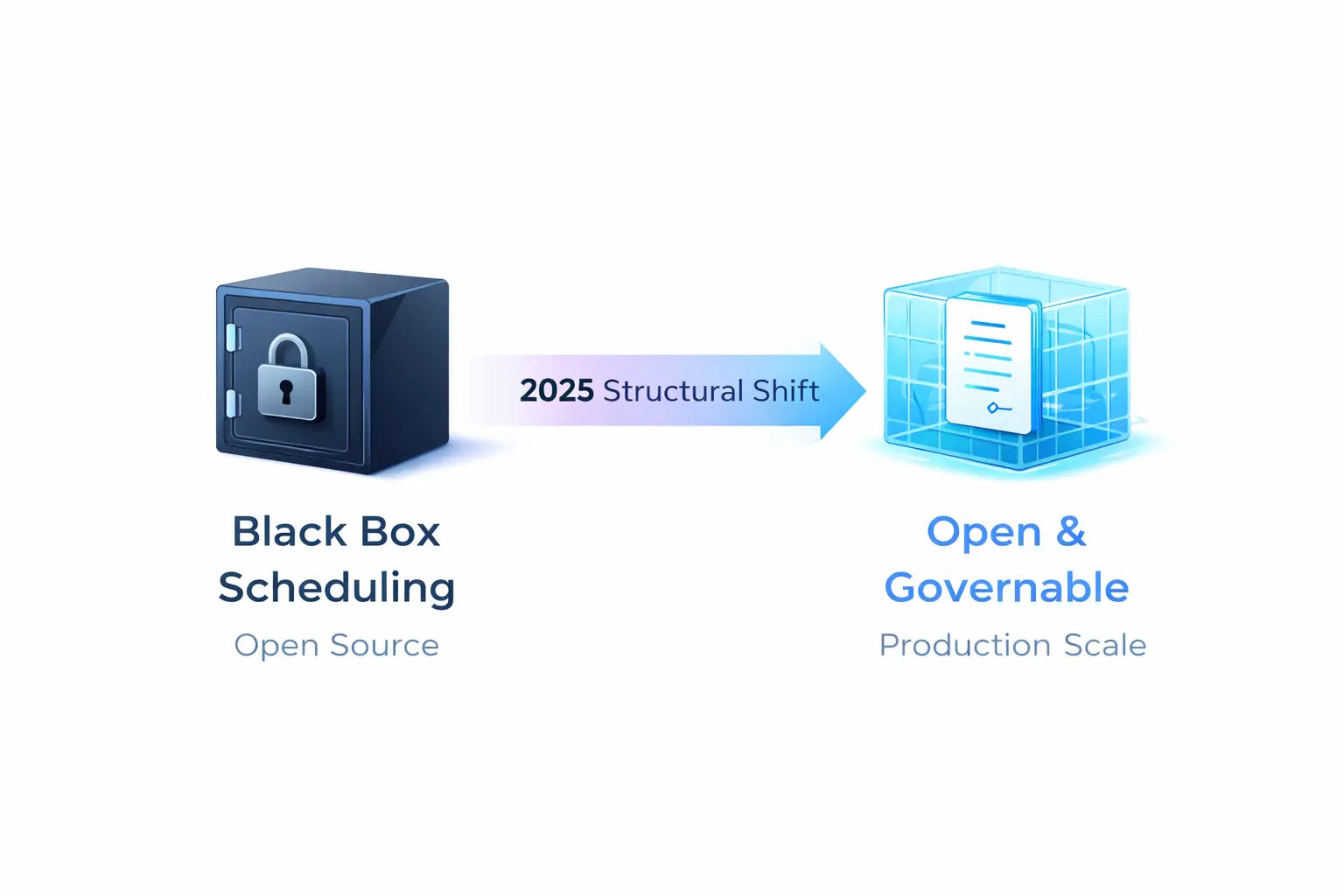

The future of GPU scheduling isn’t about whose implementation is more “black-box”—it’s about who can standardize device resource contracts into something governable.

Introduction

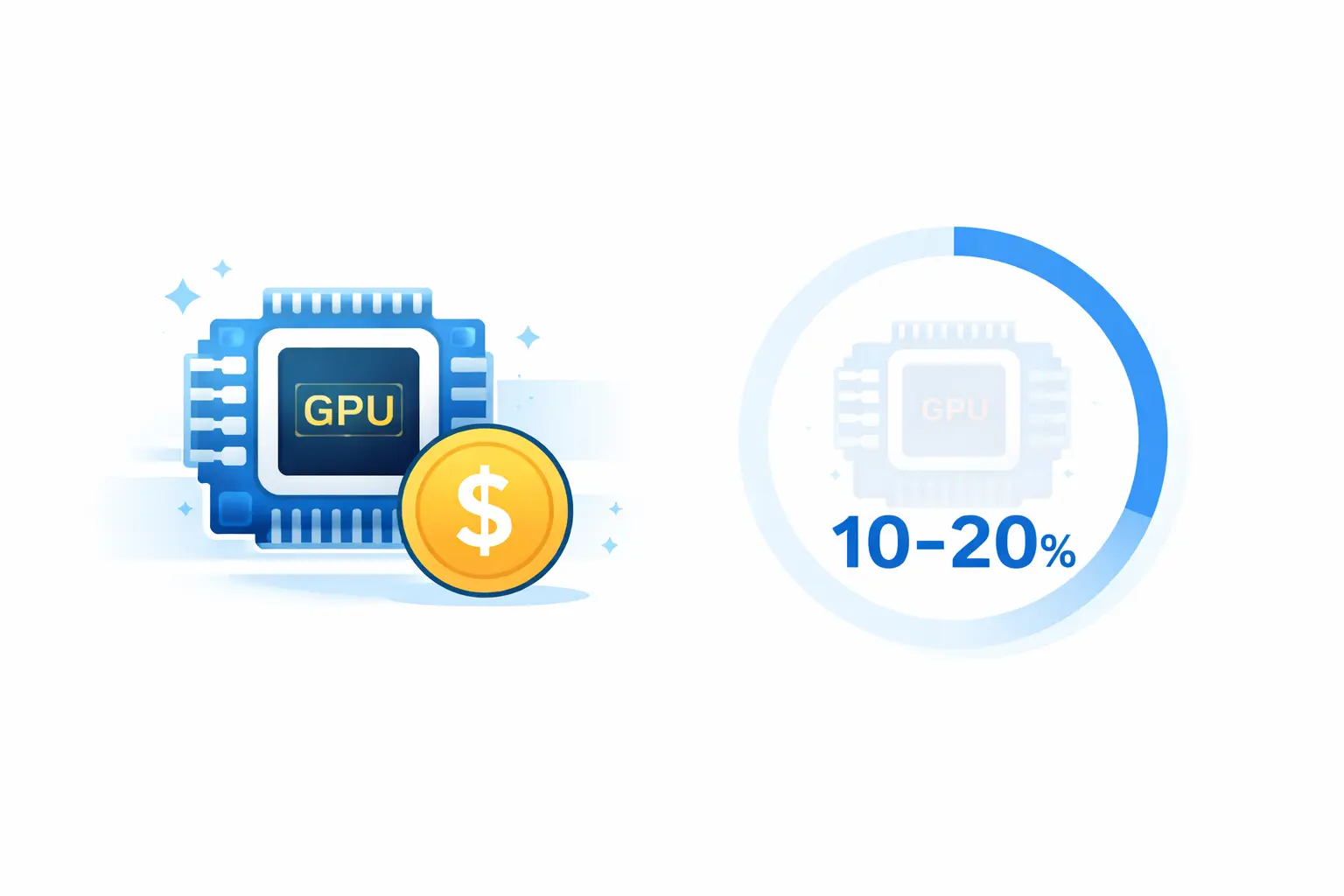

Have you ever wondered: why are GPUs so expensive, yet overall utilization often hovers around 10–20%?

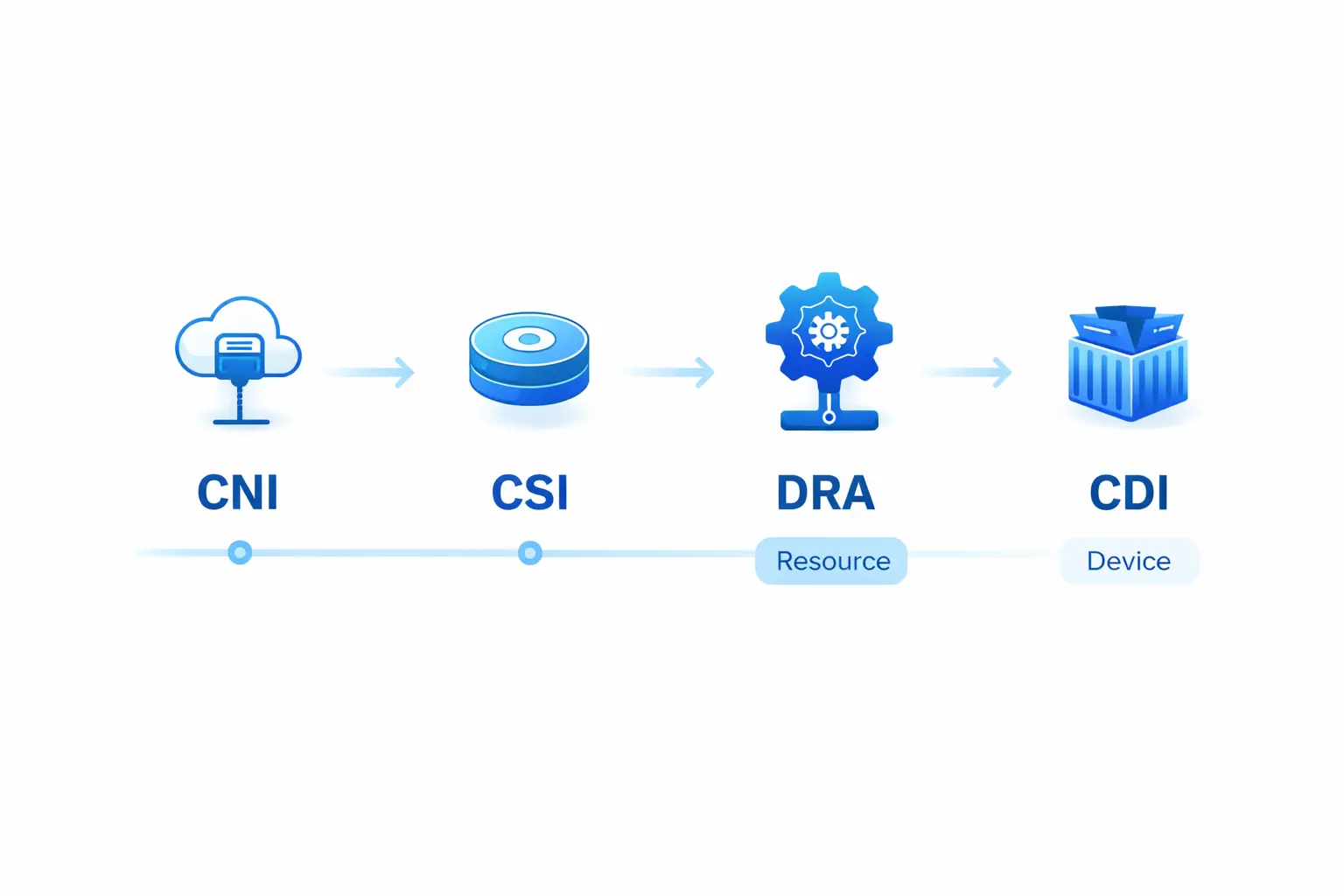

This isn’t a problem you solve with “better scheduling algorithms.” It’s a structural problem - GPU scheduling is undergoing a shift from “proprietary implementation” to “open scheduling,” similar to how networking converged on CNI and storage converged on CSI.

In the HAMi 2025 Annual Review, we noted: “HAMi 2025 is no longer just about GPU sharing tools—it’s a more structural signal: GPUs are moving toward open scheduling.”

By 2025, the signals of this shift became visible: Kubernetes Dynamic Resource Allocation (DRA) graduated to GA and became enabled by default, NVIDIA GPU Operator started defaulting to CDI (Container Device Interface), and HAMi’s production-grade case studies under CNCF are moving “GPU sharing” from experimental capability to operational excellence.

This post analyzes this structural shift from an AI Native Infrastructure perspective, and what it means for Dynamia and the industry.

Why “Open Scheduling” Matters

In multi-cloud and hybrid cloud environments, GPU model diversity significantly amplifies operational costs. One large internet company’s platform spans H200/H100/A100/V100/4090 GPUs across five clusters. If you can only allocate “whole GPUs,” resource misalignment becomes inevitable.

“Open scheduling” isn’t a slogan—it’s a set of engineering contracts being solidified into the mainstream stack.

Standardized Resource Expression

Before: GPUs were extended resources. The scheduler didn’t understand if they represented memory, compute, or device types.

Now: Kubernetes DRA provides objects like DeviceClass, ResourceClaim, and ResourceSlice. This lets drivers and cluster administrators define device categories and selection logic (including CEL-based selectors), while Kubernetes handles the full loop: match devices → bind claims → place Pods onto nodes with access to allocated devices.

Even more importantly, Kubernetes 1.34 stated that core APIs in the resource.k8s.io group graduated to GA, DRA became stable and enabled by default, and the community committed to avoiding breaking changes going forward. This means the ecosystem can invest with confidence in a stable, standard API.

Standardized Device Injection

Before: Device injection relied on vendor-specific hooks and runtime class patterns.

Now: The Container Device Interface (CDI) abstracts device injection into an open specification. NVIDIA’s Container Toolkit explicitly describes CDI as an open specification for container runtimes, and NVIDIA GPU Operator 25.10.0 defaults to enabling CDI on install/upgrade—directly leveraging runtime-native CDI support (containerd, CRI-O, etc.) for GPU injection.

This means “devices into containers” is also moving toward replaceable, standardized interfaces.

HAMi: From “Sharing Tool” to “Governable Data Plane”

On this standardization path, HAMi’s role needs redefinition: it’s not about replacing Kubernetes—it’s about turning GPU virtualization and slicing into a declarative, schedulable, governable data plane.

Data Plane Perspective

HAMi’s core contribution expands the allocatable unit from “whole GPU integers” to finer-grained shares (memory and compute), forming a complete allocation chain:

- Device discovery: Identify available GPU devices and models

- Scheduling placement: Use Scheduler Extender to make native schedulers “understand” vGPU resource models (Filter/Score/Bind phases)

- In-container enforcement: Inject share constraints into container runtime

- Metric export: Provide observable metrics for utilization, isolation, and more

This transforms “sharing” from ad-hoc “it runs” experimentation into engineering capability that can be declared in YAML, scheduled by policy, and validated by metrics.

Scheduling Mechanism: Enhancement, Not Replacement

HAMi’s scheduling doesn’t replace Kubernetes—it uses a Scheduler Extender pattern to let the native scheduler understand vGPU resource models:

- Filter: Filter nodes based on memory, compute, device type, topology, and other constraints

- Score: Apply configurable policies like binpack, spread, topology-aware scoring

- Bind: Complete final device-to-Pod binding

This architecture positions HAMi naturally as an execution layer under higher-level “AI control planes” (queuing, quotas, priorities)—working alongside Volcano, Kueue, Koordinator, and others.

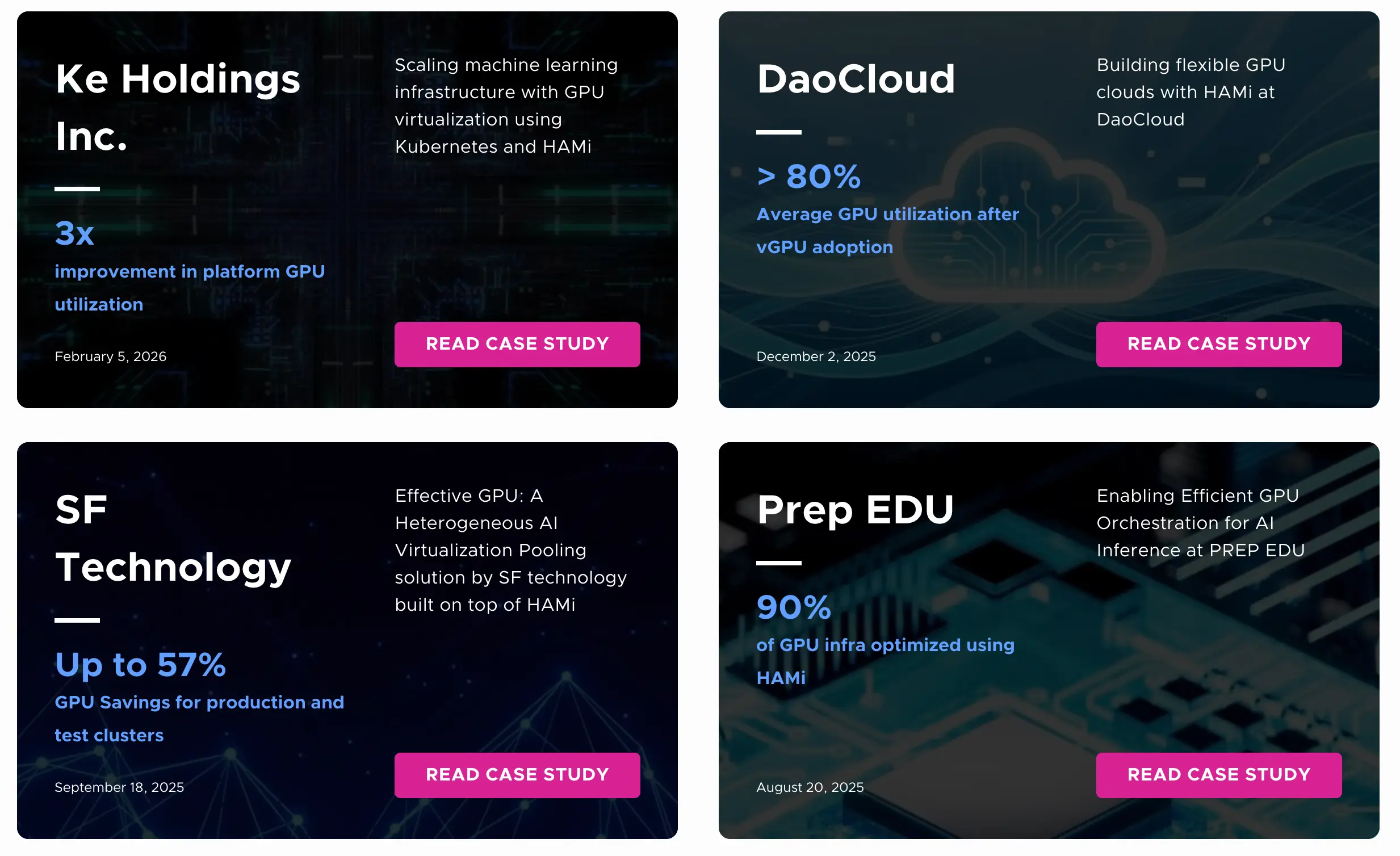

Production Evidence: From “Can We Share?” to “Can We Operate?”

CNCF public case studies provide concrete answers: in a hybrid, multi-cloud platform built on Kubernetes and HAMi, 10,000+ Pods run concurrently, and GPU utilization improves from 13% to 37% (nearly 3×).

Here are highlights from several cases:

Case Study 1: Ke Holdings (February 5, 2026)

- Environment: 5 clusters spanning public and private clouds

- GPU models: H200/H100/A100/V100/4090 and more

- Architecture: Separate “GPU clusters” for large training tasks (dedicated allocation) vs “vGPU clusters” with HAMi fine-grained memory slicing for high-density inference

- Concurrent scale: 10,000+ Pods

- Outcome: Overall GPU utilization improved from 13% to 37% (nearly 3×)

Case Study 2: DaoCloud (December 2, 2025)

- Hard constraints: Must remain cloud-native, vendor-agnostic, and compatible with CNCF toolchain

- Adoption outcomes:

- Average GPU utilization: 80%+

- GPU-related operating cost reduction: 20–30%

- Coverage: 10+ data centers, 10,000+ GPUs

- Explicit benefit: Unified abstraction layer across NVIDIA and domestic GPUs, reducing vendor dependency

Case Study 3: Prep EDU (August 20, 2025)

- Negative experience: Isolation failures in other GPU-sharing approaches caused memory conflicts and instability

- Positive outcome: HAMi’s vGPU scheduling, GPU type/UUID targeting, and compatibility with NVIDIA GPU Operator and RKE2 became decisive factors for production adoption

- Environment: Heterogeneous RTX 4070/4090 cluster

Case Study 4: SF Technology (September 18, 2025)

- Project: EffectiveGPU (built on HAMi)

- Use cases: Large model inference, test services, speech recognition, domestic AI hardware (Huawei Ascend, Baidu Kunlun, etc.)

- Outcomes:

- GPU savings: Large model inference runs 65 services on 28 GPUs (37 saved); test cluster runs 19 services on 6 GPUs (13 saved)

- Overall savings: Up to 57% GPU savings for production and test clusters

- Utilization improvement: Up to 100% GPU utilization improvement with GPU virtualization

- Highlights: Cross-node collaborative scheduling, priority-based preemption, memory over-subscription

These cases demonstrate a consistent pattern: GPU virtualization becomes economically meaningful only when it participates in a governable contract—where utilization, isolation, and policy can be expressed, measured, and improved over time.

Strategic Implications for Dynamia

From Dynamia’s perspective (and as VP of Open Source Ecosystem), the strategic value of HAMi becomes clear:

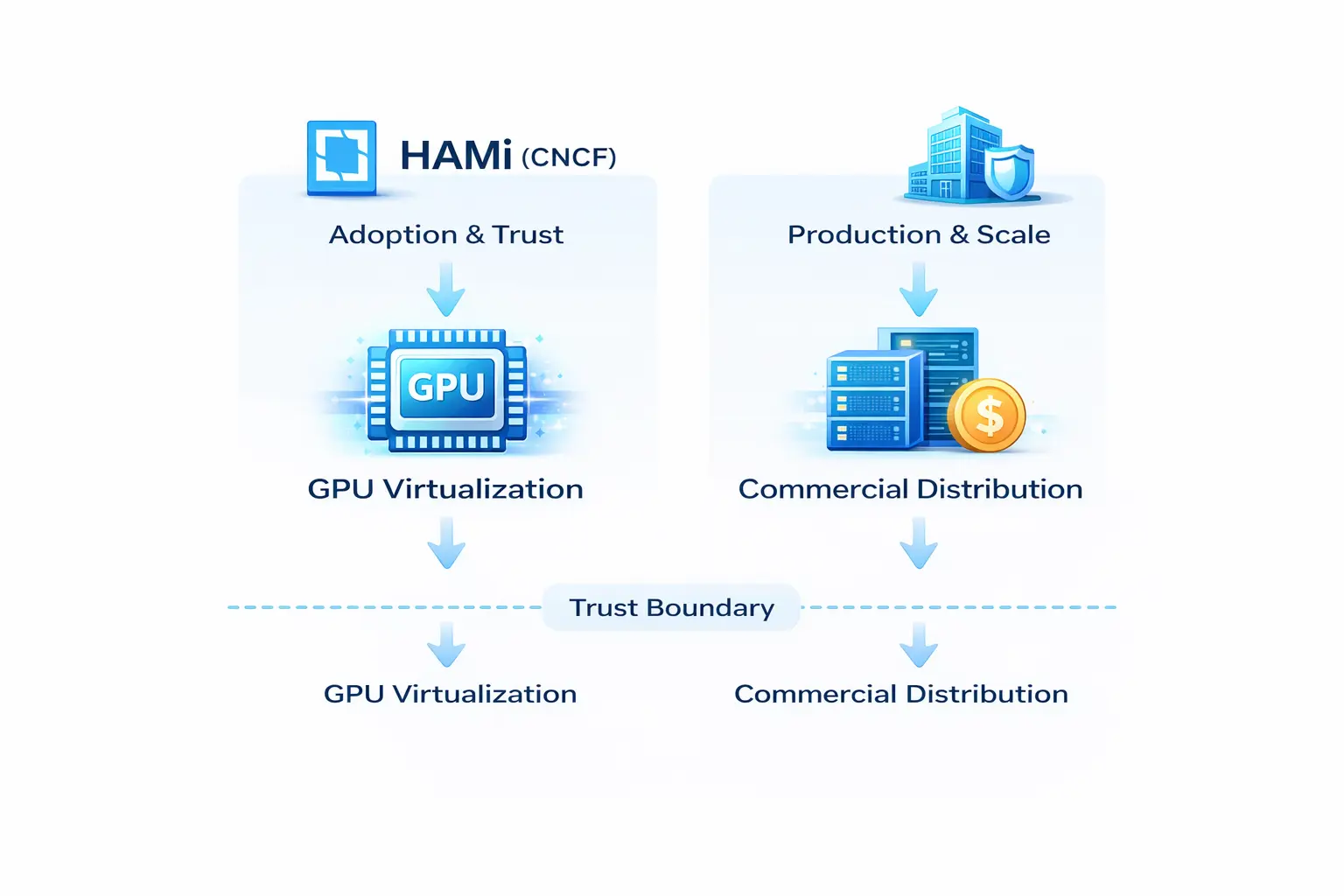

Two-Layer Architecture: Open Source vs Commercial

- HAMi (CNCF open source project): Responsible for “adoption and trust,” focused on GPU virtualization and compute efficiency

- Dynamia enterprise products and services: Responsible for “production and scale,” providing commercial distributions and enterprise services built on HAMi

This boundary is the foundation for long-term trust—project and company offerings remain separate, with commercial distributions and services built on the open source project.

Global Narrative Strategy

The internal alignment memo recommends a bilingual approach:

First layer: Lead globally with “GPU virtualization / sharing / utilization” (Chinese can directly use “GPU virtualization and heterogeneous scheduling,” but English first layer should avoid “heterogeneous” as a headline)

Second layer: When users discuss mixed GPUs or workload diversity, introduce “heterogeneous” to confirm capability boundaries—never as the opening hook

Core anchor: Maintain “HAMi (project and community) ≠ company products” as the non-negotiable baseline for long-term positioning

The Right Commercialization Landing

DaoCloud’s case study already set vendor-agnostic and CNCF toolchain compatibility as hard constraints, framing vendor dependency reduction as a business and operational benefit—not just a technical detail. Project-HAMi’s official documentation lists “avoid vendor lock” as a core value proposition.

In this context, the right commercialization landing isn’t “closed-source scheduling”—it’s productizing capabilities around real enterprise complexity:

- Systematic compatibility matrix

- SLO and tail-latency governance

- Metering for billing

- RBAC, quotas, multi-cluster governance

- Upgrade and rollback safety

- Faster path-to-production for DRA/CDI and other standardization efforts

Forward View: The Next 2–3 Years

My strong judgment: over the next 2–3 years, GPU scheduling competition will shift from “whose implementation is more black-box” to “whose contract is more open.”

The reasons are practical:

Hardware Form Factors and Supply Chains Are Diversifying

- OpenAI’s February 12, 2026 “GPT‑5.3‑Codex‑Spark” release emphasizes ultra-low latency serving, including persistent WebSockets and a dedicated serving tier on Cerebras hardware

- Large-scale GPU-backed financing announcements (for pan-European deployments) illustrate the infrastructure scale and financial engineering surrounding accelerator fleets

These signals suggest that heterogeneity will grow: mixed accelerators, mixed clouds, mixed workload types.

Low-Latency Inference Tiers Will Force Systematic Scheduling

Low-latency inference tiers (beyond just GPUs) will force resource scheduling toward “multi-accelerator, multi-layer cache, multi-class node” architectural design—scheduling must inherently be heterogeneous.

Open Scheduling Is Risk Management, Not Idealism

In this world, “open scheduling” isn’t idealism—it’s risk management. Building schedulable governable “control plane + data plane” combinations around DRA/CDI and other solidifying open interfaces, ones that are pluggable, multi-tenant governable, and co-evolvable with the ecosystem—this looks like the truly sustainable path for AI Native Infrastructure.

The next battleground isn’t “whose scheduling is smarter”—it’s “who can standardize device resource contracts into something governable.”

Conclusion

When you place HAMi 2025 back in the broader AI Native Infrastructure context, it’s no longer just the year of “GPU sharing tools”—it’s a more structural signal: GPUs are moving toward open scheduling.

The driving forces come from both ends:

- Upstream: Standards like DRA/CDI continue to solidify

- Downstream: Scale and diversity (multi-cloud, multi-model, even accelerators beyond GPUs)

For Dynamia, HAMi’s significance has transcended “GPU sharing tool”: it turns GPU virtualization and slicing into declarative, schedulable, measurable data planes—letting queues, quotas, priorities, and multi-tenancy actually close the governance loop.