The divide in technical standards and data sovereignty determines the global competitive landscape of infrastructure open source in the AI era.

In this article, I will use the differences in air quality data presentation in Apple Maps and Weather as a starting point to explore how technical standards and data sovereignty influence the open source paths of AI in different countries. I will further analyze why, in the AI era, infrastructure-level open source has become the key battleground for ecosystem dominance.

Author’s Note

This article originates from a very everyday observation: Why is air quality data in China shown as “points” in Apple Maps and Weather, while in other countries it is often displayed as “areas”?

At first glance, it seems like a product experience difference. But when I reconsidered this issue in the context of engineering, standards, and system design, I realized it actually points to a much bigger question: how different countries understand the relationship between technology, standards, openness, and sovereignty.

As an engineer who has long worked in cloud native, AI infrastructure, and open source ecosystems, I gradually realized that this difference is not limited to air quality or map data. In the AI era, it is further amplified, directly affecting how we open source models, build infrastructure, and whether we can participate in the formulation of global rules.

Writing this article is not about judging right or wrong, but about using a concrete example to explain a structural difference and discuss the long-term impact and real opportunities this difference may bring in the AI era.

What is especially important: at the level of AI infrastructure and infra-level open source, the competition has just begun. China is not without opportunities, but the choice of path will become more critical than ever.

Differences in Air Quality Data Presentation: A Microcosm of Technical Standards and Sovereignty

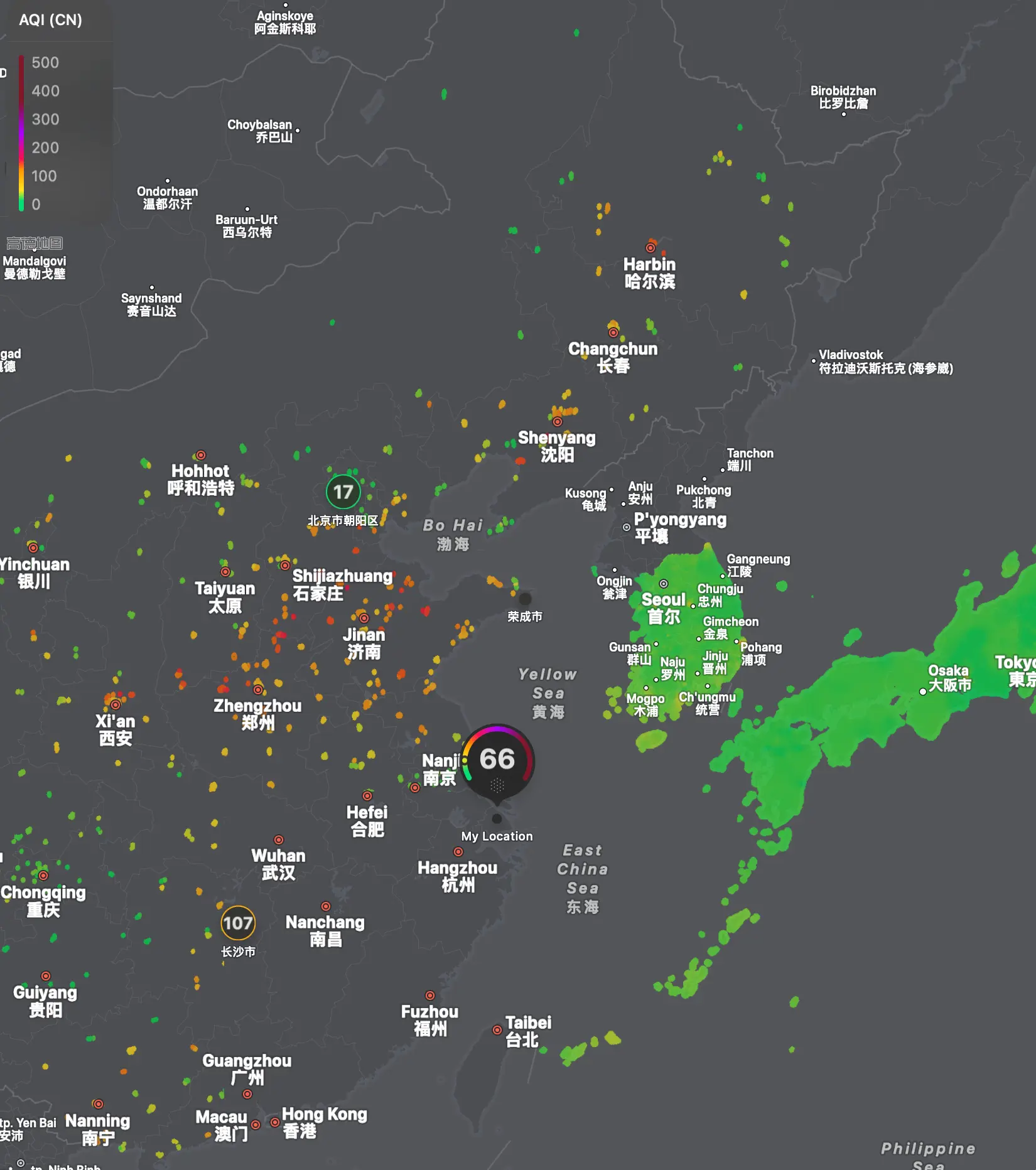

The following image illustrates the divide between spatial data, AI open source, and technical standards. By comparing how air quality data is presented in Apple Maps and Weather in different countries, you can intuitively feel the differences in technical standards and sovereignty strategies behind the scenes.

If you regularly use global products such as maps, weather, traffic, or various data services, you may notice a recurring phenomenon that is rarely discussed seriously: the way data is presented in China often differs significantly from global mainstream standards.

A very intuitive example comes from the air quality display in Apple Maps or Weather. In China, air quality is usually shown as discrete points; in the US, Europe, Japan, and other countries, it is often rendered as continuous coverage areas.

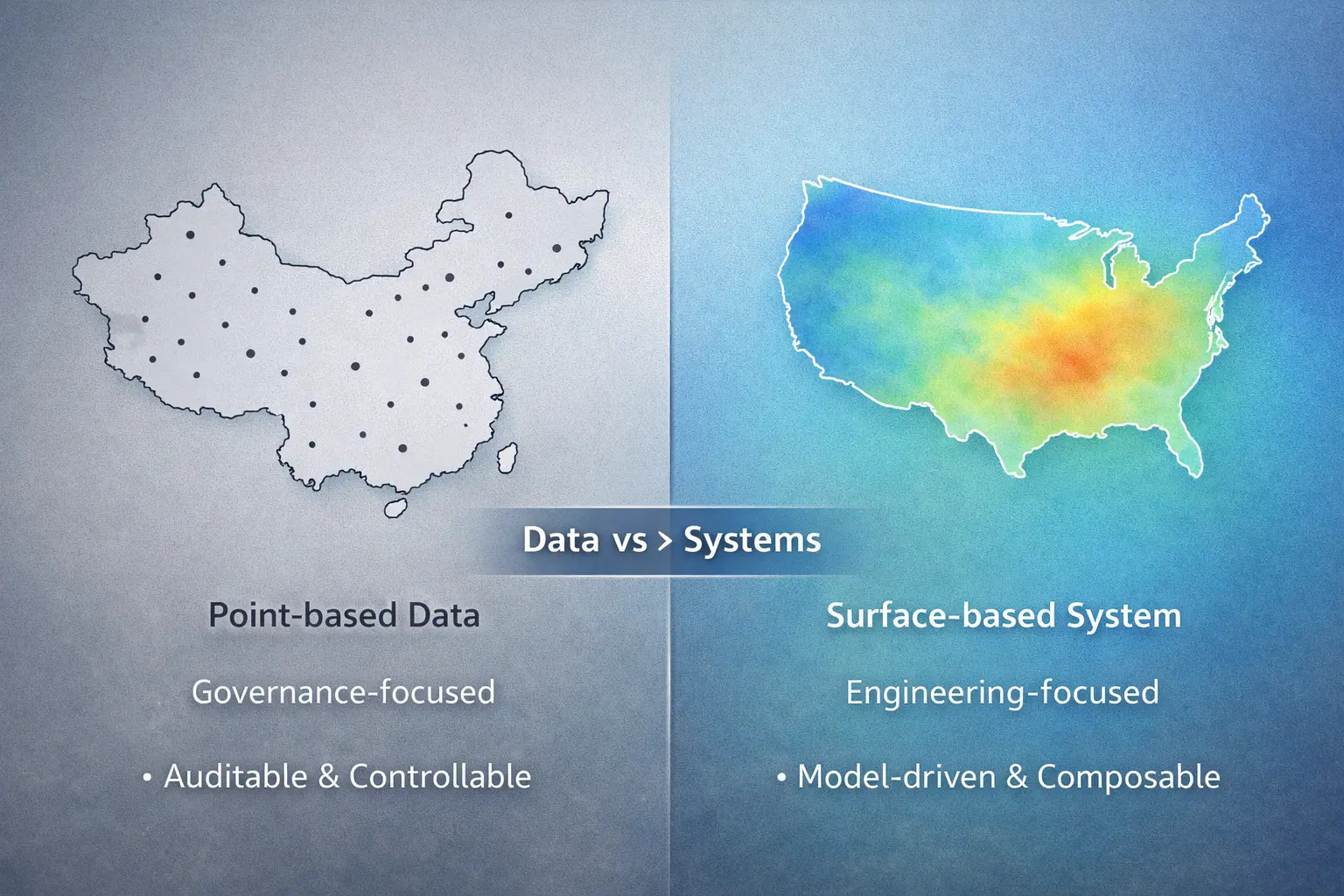

At first glance, this seems like a product experience difference, and may even lead people to mistakenly believe that “China’s data is incomplete.” But if you treat it as an engineering or system design issue, you will find: this is not a matter of data capability, but a different choice in technical standards, data sovereignty, and openness strategies.

And this choice is not limited to air quality.

Air Quality Is Just a Slice: Greater Differences in Spatial Public Data

Air quality is just a highly visible and relatively low-risk example. Similar differences have long existed in broader spatial and public data domains.

- Maps and coordinate systems

- Surveying and high-precision spatial data

- Real-time traffic and population movement

- Remote sensing, environmental, and urban operation data

In global mainstream systems, such data is usually regarded as public information infrastructure. It is standardized, gridded, API-ified, allows interpolation, modeling, and redistribution, and is widely used in research, business, and product innovation.

In China, this data often takes another form: hierarchical, discrete, strictly defined, and with centralized interpretation authority.

This is not a technical preference in a single field, but a systemic logic of technology and governance.

Three Global Paths

Placing China in a global context, we can see that there are roughly three different paths worldwide regarding “how public data and technical standards are opened.”

Engineering-Open Type: Standards and Ecosystem First

Represented by the US and some European countries, the core features of this system are:

- Public data prioritized as infrastructure

- Standards and interfaces come first

- Encourages engineering autonomy and ecosystem evolution

- Tolerates model inference and uncertainty

This path directly shaped the global landscape of foundational software and infrastructure-level open source. Linux, Kubernetes, and the cloud native system are essentially products of openness at the rules layer.

Governance-Sovereignty Type: Control and Auditability First

Represented by China, this path emphasizes:

- Sensitivity of spatial and public data

- Data as part of governance capability

- Standards, definitions, and release methods are highly bound

- Emphasizes traceability, accountability, and controllability

In this system, “point data” is not a sign of technological backwardness, but a governable technical form. When a technical system is designed as a governance system, its primary goal is not reusability, but controllability.

Compromise-Coordinated Type: Cautious Openness, Engineering Internationalization

Some countries try to find a balance between the two, maintaining caution in spatial data while being highly internationalized in engineering and industry. This shows that the difference is not about being advanced or backward, but about different objective functions.

The following diagram compares the core characteristics, typical cases, and advantages/challenges of these three paths from a global perspective. The “Engineering-Open Type” on the left shapes the global infrastructure software landscape through standards and ecosystems; the “Governance-Sovereignty Type” in the middle emphasizes data sovereignty and security controllability but has limitations in influence at the rules layer; the “Compromise-Coordinated Type” on the right attempts to find a balance between security and openness. The divide between these three paths directly affects the infrastructure competition landscape of various countries in the AI era.

The Essence of “Point” vs. “Area” in Air Quality

Among all spatial public data, air quality is an ideal observation window:

- Does not directly involve military or core economic security

- Highly visible, updated daily, and perceptible to everyone

China does not lack air quality data; on the contrary, the density of monitoring stations is among the highest in the world. The real difference lies in:

- Whether interpolation is allowed

- Whether model inference is allowed

- Whether platforms are allowed to reinterpret the data

“Point” means authenticity and traceability; “area” means models, inference, and redistribution of interpretive authority. This is precisely the watershed between technical standards and data sovereignty.

The following diagram compares two different technical paths. The left side, “Governance-Sovereignty Type,” emphasizes data traceability and controllability, using discrete point-based data presentation. The right side, “Engineering-Open Type,” allows model interpolation and inference, providing more user-friendly experience through continuous area-based coverage. The essence of this difference lies not in the level of technical capability, but in the different choices made between data sovereignty, governance capability, and open ecosystems.

The Amplification Effect in the AI Era

With the above logic in mind, many phenomena in the AI era become less confusing.

For example:

- Why are Chinese AI companies more willing to open source large language model (LLM) weights, while American companies have clearly shifted toward closed source in recent years?

- Why is foundational software and infrastructure-level open source still mainly led by the US?

The key is not “whether to open source,” but “which layer is open sourced.”

- Model weights are static, declarable assets

- Infrastructure, runtimes, protocols, and standards are dynamic, evolving system rules

Open sourcing weights is essentially openness at the asset layer; infrastructure-level open source means relinquishing control over operating rules and interpretive authority.

The following diagram compares two different layers of AI open source. The left side shows “Model Weight Layer Open Source,” which is a typical feature of Chinese path—opening static digital assets with low cost and controllable risk, but not involving rule-making. The right side shows “Infrastructure Layer Open Source,” which is a core strategy of US path—by open sourcing development tools, protocol standards, runtimes, and compute scheduling and other infrastructure, defining how AI is used, thereby mastering ecosystem rules and interpretive authority. Key insight: Open sourcing model weights does not equal mastering AI ecosystem, and the real competitive focus is shifting to the infrastructure layer of “how AI runs.”

The US Approach: Focusing on Rules and Runtime Layers

In the past year or two, US-led AI open source and ecosystem initiatives have shown a highly consistent direction: not rushing to open source the strongest models, but focusing on defining “how AI is used.”

- The Linux Foundation established AAIF (Agentic AI Foundation), focusing on AI infrastructure, standards, and toolchain collaboration

- Protocols like MCP (Model Context Protocol) aim to define common interaction methods between agents and tools/systems

- Major tech companies are generally focusing on APIs, platforms, runtimes, and ecosystem binding

The commonality of these actions: competing in model capability, but controlling the usage rules.

China’s Shift: From Model-Oriented to Infrastructure-Oriented

It is important to emphasize that this difference does not mean China is unaware of the issue.

Whether in policy discussions or within industry and research institutions, the risk of “only open sourcing models without controlling infrastructure and standard dominance” has been repeatedly discussed.

The real challenge lies in how to achieve a directional shift within the existing governance logic and risk framework. This shift has already appeared in some concrete practices.

Exploration and Practice at the Infrastructure Layer

In the AI era, infrastructure often starts with the most engineering-driven problems.

HAMi Project

Projects like HAMi do not focus on model capability, but on:

- Abstraction, allocation, and isolation of GPU resources

- How multi-tenant AI workloads are run

- How computing power transitions from hardware assets to governable system resources

The significance of such projects is not about being “SOTA,” but about entering the domain of “how AI runs.”

AI Runtime Reconstruction from a System Software Review

Exploration at the research institution level is also noteworthy. The FlagOS initiative by the Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence is a clear signal: AI is being redefined as a system software issue, not just a model or algorithm problem.

Long-Term Tech Stack Investment by Industry Players

In the industry, Huawei’s strategy reflects a similar direction: not simply open sourcing models, but attempting to build a complete, controllable AI tech stack, from computing power to frameworks, platforms, and ecosystems. This is a slower, heavier, but more infrastructure-competitive path.

Realistic Assessment: The Starting Point of AI Infrastructure Competition

Taking a longer view, we find an easily overlooked fact:

At the level of AI infrastructure and infra-level open source, there is no settled pattern between China and the US.

The US advantage lies in:

- Mature engineering culture

- Standard organizations and foundation mechanisms

- High proficiency in openness at the rules layer

China’s variables include:

- Huge AI application scenarios

- Extreme demand for computing power and system efficiency

- Ongoing directional adjustments

The real uncertainty is not “whether we can catch up,” but whether it is possible to gradually open up space for engineering autonomy and standard co-construction while maintaining governance bottom lines.

Summary

The “points” and “areas” of air quality, model weights and the world of operations—behind these appearances lies not a simple technical route dispute, but how a country finds its own balance between openness, standards, and sovereignty.

In the AI era, this issue will not disappear, but will become more concrete and more engineering-driven. And this is precisely where there are still opportunities for China’s AI infrastructure open source.